A Des Moines Register Investigation

Sixteen people will likely go missing in Iowa today.

They will join an ever-changing procession of names and thumbnail descriptions of 350 or so Iowans who populate the state’s missing-person list on any given day.

Each could be a tragedy — found murdered, like Kathlynn Shepard of Dayton and the cousins who went missing in Evansdale, or never found at all, like West Des Moines paperboy Johnny Gosch and Mason City TV anchor Jodi Huisentruit.

Far more likely, though, is that most will be located so easily that calling their cases “solved” rates as an overstatement.

Missing kids will be found hiding under beds. Runaway teens will get hungry and return home. Adults will turn up across state lines, not really missing, but not looking to be found, either.

The ease with which most cases close blunts local police responses to missing-person reports. That reality frustrates families and state law enforcement alike.

- Iowa’s missing: A page with resources, information, videos and stories at DesMoinesRegister.com/missing

- Database: Persons reported missing in Iowa

A Des Moines Register examination of missing-person cases revealed ongoing shortcomings in how Iowa responds when its residents vanish.

Among them:

+ Some local police agencies essentially ignore many missing-person cases, especially those deemed to be runaways. The agencies expend minimal resources on all but the most dire and attention-grabbing.

+ Missing adults, too, appear to get little attention, even those considered to be in danger or who have mental or physical disabilities. Of the nearly 150 Iowans missing for a year or longer, 88 are adults, most of whom are listed as disappearing involuntarily or considered in danger or are physically or mentally disabled.

+ The missing-person list is often out of date and lacks the kind of information, such as detailed descriptions and photographs, that would assist in finding the missing.

+ Some police and sheriff departments do little follow-through. Ongoing investigations consist of little more than calls to family members to determine whether the person missing has returned.

While state records indicate that the vast majority of missing-person cases are resolved within a month, some Iowans have been gone months, years, even decades.

“It’s a challenge for law enforcement to stay equally vigilant,” acknowledged Gerard Meyers, assistant director of the Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation. “We all know that it’s human nature to let your guard down.”

Almost 6,000 a year go missing in Iowa

Over the past decade, law enforcement agencies statewide have taken more than 58,000 missing-person reports, an average of almost 6,000 a year and 16 every day. At any given time, more than 300 such cases are active across the state.

The data — compiled by the state’s Missing Person Information Clearinghouse and analyzed this summer by the Register — underscore that the cases getting the most publicity also are among the rarest.

Child abductions like the Shepard case in Dayton last spring and gone-without-a-trace disappearances like that of Huisentruit, a Mason City TV anchor who vanished in 1995, are sensational outliers in a vast and messy data set.

Missing Persons of Iowa (Source: Des Moines Register)

The majority of reported cases involving teenagers are presumed to be runaways. The newspaper’s analysis of 341 missing-person cases active as of Aug. 5 found that 205 were classified as juveniles, a broad category that encompasses everyone under 18 not deemed disabled, endangered or thought to be missing involuntarily. Almost all minors are placed in that category — rightly or wrongly, the Register found.

Consider the case of Shepard, the 15-year-old who was abducted from Dayton on May 20 as she and a 12-year-old schoolmate walked home from the school bus.

Police say Michael James Klunder, 42, lured the two girls into his truck and took them to a hog confinement lot where he worked. The younger girl managed to escape. Klunder then killed Shepard before killing himself. Shepard’s body was not found until nearly three weeks later, on June 7 in the Des Moines River.

Despite an intensive, weeks-long search throughout the area, Shepard’s case remained classified in the state’s database as “juvenile” — not an involuntary disappearance — until the day her body was discovered.

Shepard was initially classified as a juvenile before the facts of the case were fully known, Webster County Sheriff James Stubbs said. Once it was known she had been abducted, authorities were too busy with the investigation to update that aspect of the case record.

“It was never changed, but then again, I’m not sure what difference it would’ve made,” Stubbs said. “There was enough things going on that nobody probably thought of that.”

The information is imprecise, outdated

DCI officials acknowledge the missing-person database often provides an imprecise and sometimes inaccurate picture of who is and is not missing.

Although his agency maintains the database and posts it on the Internet, Meyers stressed that the DCI relies on local law enforcement agencies to report and update missing-person cases. Some agencies are more vigilant than others, he said.

And in some cases, local police, too, are left in the dark about whether a person is still gone. That’s because family and friends who filed the initial report don’t always contact police when that person later turns up or phones to reassure them they are OK, Meyers said.

Until recently, the DCI had a dedicated cold cases team that focused on unsolved homicides and missing-person cases. The federal funding for it expired in 2011.

Meyers said the agency still reviews dormant cases regularly in pursuit of new leads or to apply newly available technology, but can’t constantly monitor them.

Even a missing-person advocate empathizes with the workload police agencies face.

“We ask law enforcement to do an awful lot for us — protecting communities and responding to violent crimes …,” said Robert Lowery, a senior executive director at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. “Sometimes missing children, especially runaway children, are a lower priority because of the urgencies of the other demands placed on them.”

Case type, intuition influence response

From 2008 to 2012, minors accounted for almost 86 percent of missing-person cases reported in Iowa. Of those, 85 percent were 14- to 17-year-olds, often bolting from dysfunctional homes or social service agencies.

Such cases are generally resolved quickly: From 2008 to 2010, roughly 75 percent of missing-person cases were resolved within a week, and about 86 percent were closed within a month.

Police are aware of these numbers, and tailor responses accordingly.

In Des Moines, a young child who is missing typically gets top priority, drawing multiple patrol cars into a search that continues until the youngster is found, said police spokesman Sgt. Jason Halifax.

For teenage runaways and missing adults, however, the response relies heavily on investigators’ judgment and intuition. Officers on patrol hustle to get the missing person’s name uploaded into a national law enforcement database, ensuring the person will be recognized as missing if found in other jurisdictions.

Beyond that, though, it’s up to a detective to decide whether a case is, in Halifax’s words, “fishy” enough to pursue.

“People think we really beat the bushes for missing folks, but we don’t have the manpower to do a lot of that,” Halifax said. He added, “If a kid, an adult or anyone wants to be gone, we may not find them.”

Sampling shows little follow-up A sampling of active missing-person cases from Davenport showed little investigative initiative by police and widespread record-keeping problems.

Among 25 active missing-person cases reviewed by the Register in July, 14 weren’t actually active.

Follow-ups conducted by Davenport police in response to the Register’s request showed 10 instances in which the individuals had been located, but their status hadn’t been updated in the national missing-person database. In the four other cases, including one dating to March 2012, authorities simply hadn’t followed up with the family to confirm the person had returned.

The remaining 11 unsolved cases raise questions about the quality of police investigations into some of Iowa’s missing persons.

In each case, records show limited and sporadic attempts by police to contact the families by phone. If a call went unanswered or the line was disconnected, that result was recorded in the case file and no further action was taken. The person was assumed to still be missing.

Human traffickers target runaways

Although it’s common for law enforcement agencies to place low priority on missing-person cases, especially runaways, that practice troubles state authorities, social service workers and the families of those who have disappeared.

One reason was apparent last month, when a nationwide crackdown on human trafficking operations rescued more than 100 exploited children — many of them runaways — and arrested 150 human traffickers. The bust underscored law enforcement’s new emphasis on human trafficking and revealed the reach of the phenomenon, in which victims are coerced into labor or sex for money. Thirty-three of the arrests occurred in Council Bluffs, Omaha and Lincoln, Neb.

Brittany Phillips knows firsthand what it’s like to be rescued from such an operation. After running away from an Iowa City group home at age 15, Phillips was taken to Chicago by human traffickers and forced into prostitution. Unlike many caught up in trafficking, she was rescued by an undercover police officer and reunited with family.

Phillips, now 21, has worked to raise awareness about trafficking and has helped lobby for stricter penalties for traffickers.

She said law enforcement and social service agencies alike should be better attuned to the issue.

“Right now, I think they’re lacking in what they’re doing,” she said.

Critic: Local police ‘write the kids off’

Carolyn Pospisil’s stepdaughter Erin went missing from Cedar Rapids in 2001, at age 15.

Initially classified as a runaway, the case has gone nowhere in the 12 years that followed.

“The police department automatically assumes that any child over the age of 14 is a runaway, or at least they did at the time,” Carolyn Pospisil said in an interview last month. “And in doing so, they basically write the kids off. I know that may not be their intent, but that’s what happens.”

A lieutenant in the department’s investigations division disputed that characterization. The case remains open, with a detective assigned to it, said Lt. Craig Furnish. Internal reviews and investigations into tips occur at least annually.

Regardless, no case-breaking leads have materialized in more than a decade, and the whereabouts of Erin Pospisil — or even knowing whether she’s alive or dead — remain a mystery.

It’s a similar story in one of Des Moines’ longest unsolved missing-person cases.

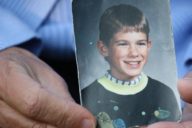

Marc Allen disappeared in 1986, at age 13, after leaving his mother’s southside home to visit a friend down the street.

The police followed up on leads immediately after Marc went missing, and have continued to check in with the family every few years, said his mother, Nancy Allen. But she also wondered whether authorities might have done more had circumstances been different.

“I think they feel that kids that are that age just take off, that it’s not a situation where they were taken by anybody,” she said. “And, of course, unless you find them, you don’t know whether they were or not.”

Shadow image: Mysterious Universe